Johannes Kepler wanted circles.

As a devout Christian, he believed that God—the supreme geometer—would craft the heavens with mathematical perfection. And what shape is more perfect than a circle? For two thousand years, astronomers had agreed: celestial bodies move in circular orbits. Kepler saw no reason to question this assumption.

There was just one problem. Mars refused to cooperate.

The Data That Would Not Yield

Kepler possessed something no astronomer before him had ever obtained: twenty years of meticulous planetary observations compiled by Tycho Brahe, amazingly with only the naked-eye. Tycho’s measurements were accurate to within two minutes of arc—an unprecedented precision for the time.

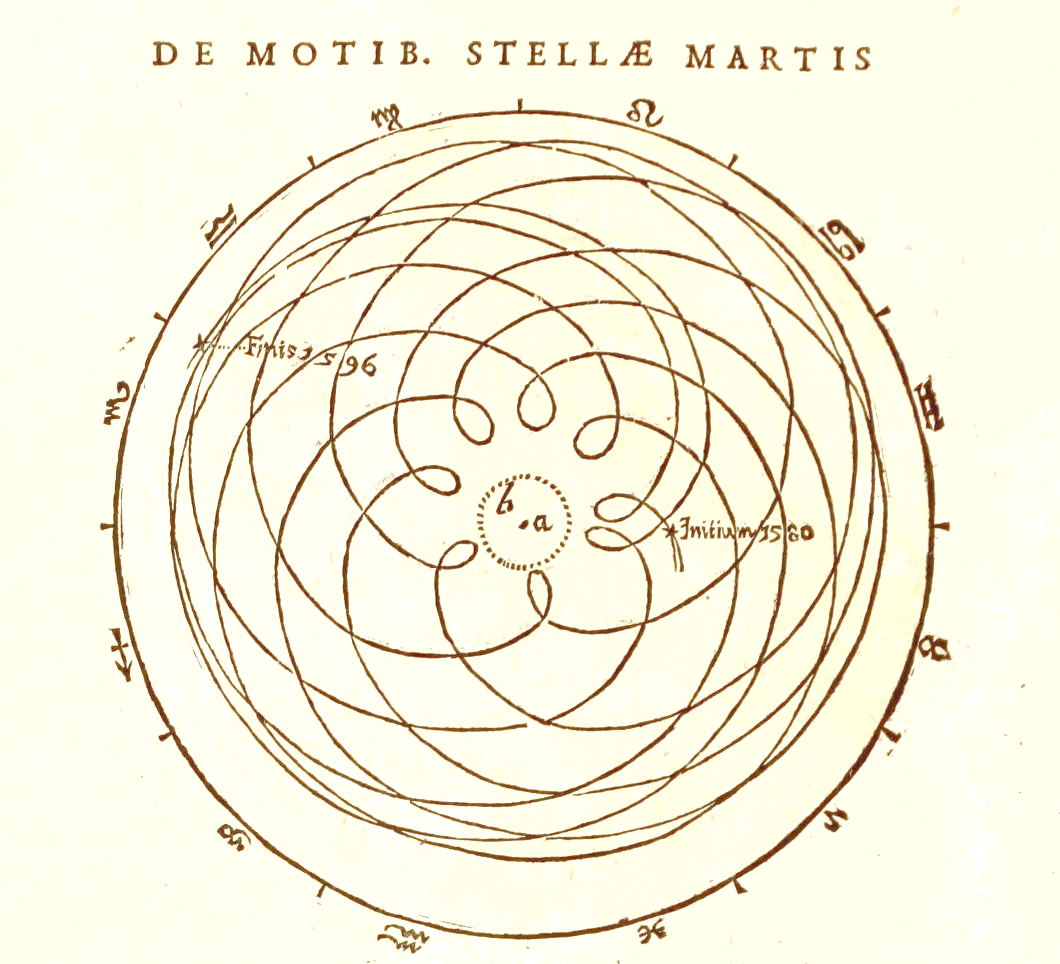

Using this extraordinary data, Kepler spent years attempting to model Mars’s orbit as a circle. He tried circle after circle. He added epicycles. He adjusted parameters. He performed calculations by hand that would take a modern computer mere seconds but cost him months of labor.

Nothing worked.

The best circular model he could construct still produced an eight-minute discrepancy between where Mars should appear and where Tycho’s data showed it actually was. Eight minutes of arc—just eight-sixtieths of a single degree. A sliver so small that earlier astronomers would have dismissed it as observational error.

Kepler could not dismiss it.

Why Eight Minutes Mattered

Here is the point at which Kepler’s intellectual humility changed history. In his Astronomia Nova (1609), he wrote:

Since divine benevolence has bestowed on us Tycho Brahe, a most diligent observer, from whose observations this eight-minute error is deduced, it is fitting that we accept with grateful minds this gift from God… For if I had thought I could ignore eight minutes of longitude, I would already have made enough of a correction in the hypothesis. Now, because they could not be disregarded, these eight minutes alone will lead us along a path to the reform of the whole of Astronomy.1

Consider the weight of this statement. Kepler had invested years constructing his circular model. His career, his reputation, and his theological intuitions all pointed toward circles. He was eight minutes away from declaring victory.

But he didn’t ignore it.

Instead of dismissing the data, Kepler dismissed his assumption. He abandoned circles entirely and began testing other shapes. Eventually, he discovered that Mars moves in an ellipse—an elongated oval with the Sun at one focus. This became Kepler’s First Law of Planetary Motion, the foundation upon which all modern astronomy rests.

The Harder Lesson

It is easy to admire Kepler from a distance. Of course he followed the evidence—that is what good scientists do. But consider what this cost him. He had to admit that his beautiful theological intuition—that God creates perfect circles—was mistaken. He had to discard years of painstaking work. He had to accept a shape that felt less elegant, less divine, less right.

This is exactly what philosopher Étienne Gilson means in methodical realism. It is the discipline of letting reality correct our expectations. We should not force reality to conform to our preferred ideas. It sounds simple. In practice, it is difficult.

Science today has its circles—assumptions so deeply embedded in our thinking that we scarcely notice them. When the data pushes back, our first instinct is to protect the model, not to question it. Kepler’s eight-minute error reminds us that the smallest discrepancies sometimes matter most.

The question is whether we possess the humility to let them.

This post explores ideas developed more fully in The Impossible Revolution: Why It Took a Century to See What Was Obvious.

Footnotes

Johannes Kepler, Astronomia Nova (1609), Chapter 19. Translation from William H. Donahue, New Astronomy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 286. ↩