One hundred and forty years.

It took humanity a long time to accept a simple fact: the Earth orbits the Sun, not the reverse.

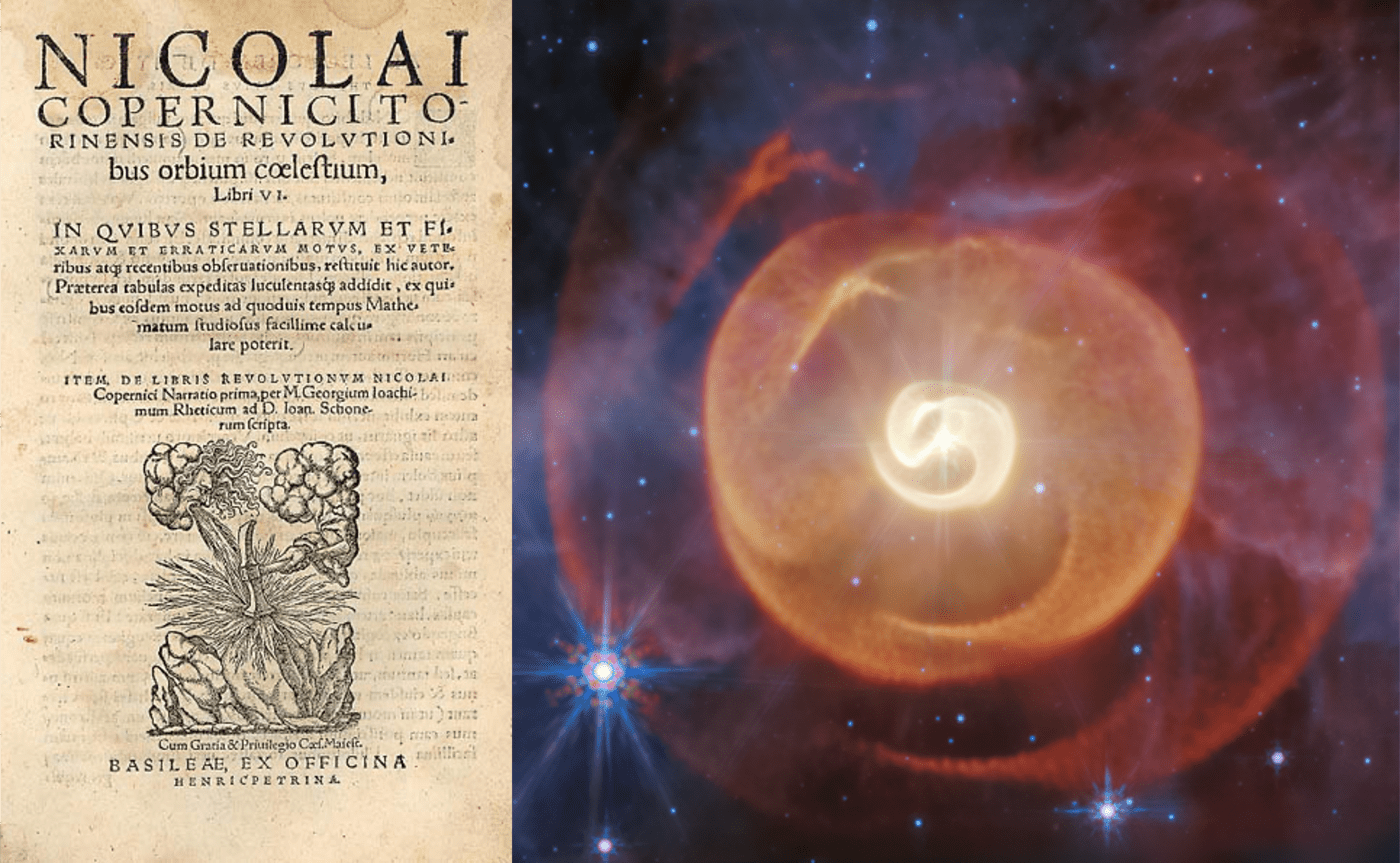

Think about that time span. Copernicus published De revolutionibus in 1543. Newton’s Principia appeared in 1687. Five generations lived and died in between. Entire academic careers were built defending geocentrism. Brilliant minds—men who could read Greek, do trigonometry, and navigate by the stars—went to their graves convinced the Sun circled the Earth.

Why did it take so long? The standard answer is simple: religious dogma suppressed scientific truth. But that story is a modern fiction, and it obscures something far more important.

The real question is not why geocentrism survived so long. The real question is why heliocentrism succeeded at all.

The Mystery No One Explains

We are taught that science progresses through a neutral “scientific method”: observe, hypothesize, test, repeat. Follow the evidence wherever it leads. If this were true, the Scientific Revolution should have been straightforward. Better telescopes appeared. Better data accumulated. Smart people looked at the evidence and changed their minds.

But that’s not what happened.

What actually happened was far stranger, and far more contingent. The shift to heliocentrism required several philosophical commitments. These commitments were not obvious and not neutral. In the ancient world, they almost never occurred together. The historian of science Stanley Jaki spent his career documenting a troubling fact. Science was stillborn in every major civilization except Christian Europe.[1]

This isn’t because other cultures lacked intelligence or curiosity. The Greeks had geometry. The Chinese had technology. The Babylonians had astronomy. The Islamic world preserved and advanced ancient learning.

Yet in none of these cultures did science achieve what is regarded as science today. It lacked the ability to build cumulative, self-correcting knowledge. This type of knowledge generates reliable predictions and transforms the world.

Why? What was missing?

The Stillbirth of Science

Stanley Jaki’s thesis is simple but disturbing: science requires a very specific theological foundation. You cannot do physics if you worship the cosmos.

In ancient Greece, the universe was eternal and cyclical. Aristotle believed in an infinite regress of causes, with no true beginning. The Stoics taught that the cosmos was itself divine—a living, rational animal. Under these assumptions, why would you test nature? You don’t interrogate a god. You contemplate it. You submit to its eternal cycles.

In China, the cosmos was governed by the Tao—an impersonal, indefinable principle that transcended rationality. The idea of mathematical laws that could be discovered and written down made no sense. Nature was too subtle, too organic, and too fluid for this rigidity.

In India, the material world was maya—illusion. Ultimate reality lay beyond the physical. Why would you spend a lifetime measuring planetary orbits if the cosmos itself was a veil to be transcended?

Even in Islam, where scholars like Al-Biruni and Ibn al-Haytham made stunning advances, science eventually stalled. Jaki argues that a lack of trust in the regularities of nature prevailed.

Only in Christian Europe did a peculiar combination of ideas converge:

- The cosmos is created, not eternal. There was a beginning. Things could have been otherwise.

- The cosmos is rational, not chaotic. God is Logos—Word, Reason, Order.

- The cosmos is contingent, not necessary. God was free to create any universe He wanted. You can’t deduce what exists from pure logic. You must go look.

Jaki and Thomas F. Torrance cited these as an appeal to “faith in a contingent, rational order.” It sounds abstract, but it had immense practical consequences.

If the universe is a contingent creation, then it must be investigated empirically. You can’t just sit in a chair and reason about what must be true (as the a apriorists tried). You must observe, build telescopes, measure planets, and see what God actually made.

This was not obvious. It was not inevitable. And it happened only once.

The Personal Knowledge of Discovery

But even granting the right theology, something else was required: a particular kind of person.

The chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi argued that the positivist myth of the “neutral observer” was not just wrong. It was the opposite of how discovery works. In an amazing work, Personal Knowledge, Polanyi showed that science is not a mechanical process. It is an act of intellectual passion.

To discover something new, you must commit to a vision of reality that cannot yet be proven. You must “indwell” your theory, seeing patterns no one else sees, guided by what Polanyi called tacit knowledge[2]. This is an inarticulate sense that something must be true, even if you can’t yet prove it.

Copernicus had this. He didn’t have better data than Ptolemy. In fact, his original model was worse at predicting planetary positions. But he sought mathematical harmony. He committed himself to heliocentrism not because the evidence forced him, but because of a tacit sense of cosmic order.

This is what Polanyi meant by personal knowledge. Science is not impersonal. It is fiduciarily rooted [3]—grounded in an act of faith that reality is intelligible and worth pursuing.

But this creates a problem: how do you know your tacit intuitions are right and not just wishful thinking?

The Discipline of Realism

This is where Étienne Gilson’s philosophy becomes essential. Gilson championed what he called Methodical Realism. This is the discipline of letting the thing-in-itself dictate your thoughts. It avoids forcing reality to fit your preferred mental models.

Before the Scientific Revolution, astronomy operated under a philosophy called “saving the appearances.” [4] It didn’t matter if your model was true. What mattered was whether it predicted eclipses and made calendars work. Ptolemy’s epicycles were just mathematical tools. The question wasn’t whether the planets really moved that way.

Copernicus shattered this. He didn’t just offer better math (he didn’t have it). He made a Realist claim: the Earth really moves. The Sun really stands still. This is not a convenient fiction. This is what exists.

This was philosophically radical. It meant that human minds can grasp the structure of reality itself—not just useful approximations, but truth.

But realism is hard. It requires intellectual humility. You must be willing to let nature destroy your most cherished ideas.

Kepler experienced this agony firsthand. For years, he tried to fit Mars’s orbit into a circle. He believed God would create perfect circles. But the data kept refusing. Finally, after exhausting every circular model, Kepler had to confront an eight-minute discrepancy [5] in Tycho Brahe’s observations.

Eight minutes of arc. A margin too small for most astronomers to care about.

But Kepler’s commitment to realism would not let him ignore it. If the data said the orbit wasn’t circular, then it wasn’t circular, no matter how much he wanted it to be.

Instead, Kepler surrendered to the ellipse.

This is what Gilson meant by methodical realism. You let the nature of the thing correct your expectations. You do not impose your preferred geometries onto reality. You listen.

Thinking According to Nature

The Reformed theologian Thomas F. Torrance gave this listening a name: kataphysic inquiry [6]—thinking kata physin, “according to nature.”

Torrance argued that true science is an act of obedience. Not obedience to authority, but obedience to the thing being studied. You cannot dictate terms to reality. If light behaves as both particle and wave, your job is not to deny the paradox. Your job is to expand your mind until you can hold the paradox.

The Aristotelians who refused to look through Galileo’s telescope were not defending reason. They were defending a philosophical system that told them what must be real. They already “knew” that the heavens were perfect and unchanging. So when Galileo claimed to see mountains on the Moon and spots on the Sun, they dismissed him without looking.

But Galileo practiced kataphysic humility. He let Jupiter’s moons tell him what the universe was like. He didn’t ask, “What must be there?” He asked, “What is there?”

This sounds simple. Yet is distressingly difficult.

The Revolutionary’s Loneliness

Here is what it cost:

Copernicus waited until he was on his deathbed to publish, knowing his ideas would bring ridicule (or worse).

Kepler lived in poverty, driven only by a mystical belief in the “music of the spheres.”

Galileo faced the Inquisition and spent his final years under house arrest. (Some of this was his fault.)

Newton worked in isolation, risking mental breakdown, driven by theological and alchemical obsessions that would have appalled his contemporaries.

None of them did this for career advancement. They couldn’t. The institutions of their day opposed them.

They did it because they were gripped by “intellectual passion,” a term coined by Polanyi. This heuristic vision pulled them forward, even when the evidence was incomplete. The cost is sometimes high.

And even after they succeeded, the world did not immediately believe them.

Geocentrism remained the dominant view in universities for decades after Newton. Why? Not because the evidence was ambiguous. By 1700, the evidence was overwhelming. The problem was philosophical inertia.

The old guard had spent their careers mastering epicycles. Their reputations, their textbooks, their sense of intellectual identity were all invested in the Ptolemaic system. To accept heliocentrism meant admitting that their life’s work was built on a mistake.

So they didn’t.

What This Means for Origins

Now apply this to the modern debate over life’s origins.

But we must be careful here since this is far more difficult. The path forward is not to replicate the mistakes of those who confuse philosophical and scientific levels of discourse. There are several important components.

- Jaki’s Crucial Distinction

Stanley Jaki distinguished implications of science for philosophy:

The Philosophical Argument from Contingency: We observe the specificity of all things in their particular forms. These forms have distinct properties and limitations. They all “cry out for a cause.”[7] An endless chain of causes would lead to infinite regress. Therefore, theology and reason conclude that creation ex nihilo occurred. It was an act performed “only once.” This act relates to the coming into being of all, regardless of its moment.

This is a metaphysical demonstration. It reasons from the contingency of everything that exists to a First, Necessary, Intelligent, Creative Cause. This is not a “God of the gaps.” It is a philosophical recognition that existence itself requires explanation.

Additionally, matter operates according to its forms and within its natural laws. God’s intelligence is revealed in His choice of this specific universe with its particular laws, material structures, and initial conditions. This choice was a divine act of freedom that made empirical science possible in the first place.

2. Polanyi’s Boundary Conditions

But doesn’t this reduce life to “mere chemistry”? No. Polanyi’s concept of boundary conditions [8] is key.

In his 1968 article “Life’s Irreducible Structure” published in Science, Polanyi demonstrated that living systems exhibit hierarchical organization. This organization cannot be reduced to physics and chemistry alone. Consider DNA: the chemical bonds in nucleotides follow the laws of chemistry. However, the sequence of those nucleotides—which contains genetic information—is not determined by chemistry. The sequence is a boundary condition [9] that constrains but is not explained by lower-level laws.

This is distinguished from “irreducible complexity” in the sense of detecting violations of natural law. It is recognizing that higher organizational principles operate within—but are not reducible to—physical and chemical regularities.

The question is not whether biological systems follow natural laws (they do). The true inquiry is whether the informational content and organizational principles manifest in life point toward the purposeful creation of the entire natural order.

3. Torrance’s Divine and Contingent Order

Thomas Torrance’s Divine and Contingent Order [10] provides the theological framework. Torrance argued that God’s rationality is manifest in the contingent intelligibility of nature. The universe didn’t have to exist, and it didn’t have to have these particular laws. But because God freely chose to create it this way, it exhibits:

- Rational Order – It can be understood mathematically and logically

- Contingent Order – It must be investigated empirically; we can’t deduce what exists from pure reason

This means we can recognize that God’s creative intelligence is manifest in:

- The specific laws of biochemistry that make life possible

- The initial conditions of the universe and earth

- The emergent properties that arise when matter is organized in particular ways

- The deep informational structures encoded in the genome

The contingency is in the entire system.

The Stillborn Paradigms of Modernity

Science was stillborn in the ancient world because the wrong metaphysics prevented it. It could be stillborn again.

If we insist that the universe is self-caused, self-organizing, and purposeless, we risk treating this as an unquestionable dogma. Then, we are no different from the Greek philosophers who “knew” the heavens must be perfect spheres.

But we also err if we fail to seek God in the magnificent rationality of the created order itself.

The Scientific Revolution succeeded because a handful of thinkers dared to break free from the mental models of their age. They believed in a contingent, rational order. They practiced methodical realism. They thought according to nature. And they endured the loneliness of seeing truths others could not yet grasp.

We are waiting for another revolution.

The questions are visible to anyone willing to look:

- Why does the genetic code function as genuine information?

- How do boundary conditions at multiple hierarchical levels coordinate to produce living systems?

- How do we account for the fine-tuning of physical constants that make life possible?

But data alone does not cause revolutions.

Revolutions happen when minds adopt the realism that fears being wrong more than being rejected. We need scientists with the theological depth of Jaki to distinguish creation from intervention, contingency from gaps. We need philosophical insight to recognize hierarchical organization in nature. We need the clarity of Gilson to distinguish scientific and metaphysical commitments. We need the intellectual humility of Torrance. We must think according to the contingent order God actually made. We should not think according to our preferred philosophies.

The question is not whether the evidence exists.

The question is whether we have the philosophy—and the bold insight—to see it clearly.

[1] Stillborn science: Stanley Jaki documented how scientific inquiry repeatedly arose in various civilizations but failed to achieve self-sustaining development—a pattern he attributed to underlying metaphysical assumptions incompatible with experimental science. See Science and Creation (1974).

[2] Tacit knowledge: Polanyi’s term for the pre-articulate, intuitive dimension of knowing that cannot be fully formalized but guides scientific discovery. We “know more than we can tell.”

[3] Fiduciarily rooted: From Latin fiducia (faith, trust). Polanyi argued that all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, rests on commitments that cannot themselves be proven but must be trusted.

[4] Saving the appearances: The ancient astronomical practice of creating mathematical models that predicted planetary positions without claiming the models represented physical reality. From the Greek sōzein ta phainomena.

[5] Eight-minute discrepancy: Kepler discovered that Mars’s observed position differed from the predicted circular orbit by eight minutes of arc (8/60 of one degree)—a tiny difference that led him to abandon circular orbits entirely.

[6] Kataphysic inquiry: From Greek kata physin, meaning “according to nature.” Torrance’s term for scientific investigation that lets the nature of the object determine the method of study, rather than imposing external frameworks.

[7] Specificity cries out for a cause: Jaki’s philosophical argument that the particular character of any existing thing—why it is this and not something else—requires causal explanation ultimately grounded in a free, creative act.

[8] Boundary conditions: In Polanyi’s usage, constraints on physical-chemical processes that come from higher organizational levels. DNA’s nucleotide sequence is a boundary condition on chemistry—it uses chemistry but is not explained by it.

[9] Life’s irreducible structure: Polanyi’s 1968 Science article argued that living systems exhibit hierarchical organization where each level operates according to principles that constrain but are not reducible to the level below.

[10] Divine and Contingent Order: Torrance’s 1981 book arguing that God’s creative rationality produces a universe that is both intelligible (we can understand it) and contingent (it didn’t have to exist this way, so we must investigate empirically).

This essay represents the philosophical framework that guides all content at Faith and Reason-25. We believe the path forward requires neither uncritical acceptance of materialist metaphysics nor confusion of philosophical and scientific levels of discourse, but rather the rigorous realism that made the Scientific Revolution possible.

Want to explore these ideas further? Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly insights where rigorous science meets biblical faith—no easy answers, just faithful thinking grounded in the best philosophical traditions.

About the Author: Dr. Neal Doran is a paleontologist and professor specializing in the intersection of creation science and the history and philosophy of science. Drawing on thinkers like Stanley Jaki, Michael Polanyi, Étienne Gilson, and Thomas F. Torrance, he explores how Christians can engage origins questions with intellectual honesty, theological depth, and methodical realism. He partners with theologian Jud Davis on the Biblical Theology Today podcast.